Evergreen Spotlight: STARS Students Shine

Over the summer, two Greenhill seniors participated in the Science Teacher Access to Resources summer research program. The following story was featured in the November issue of The Evergreen.

|

|

|

By: Khushi Punnam, Sasha Wai

Petri dishes over pool days. Early mornings over sleeping in. Stepping into the lab instead of wading into the sea.

For two rising seniors, summer meant delving into professional biomedical research through UT Southwestern’s highly selective high school research program.

The eight-week Science Teacher Access to Resources at Southwestern – commonly known as STARS – immerses students in real-world research alongside their principal investigators at the UTSW Medical Center.

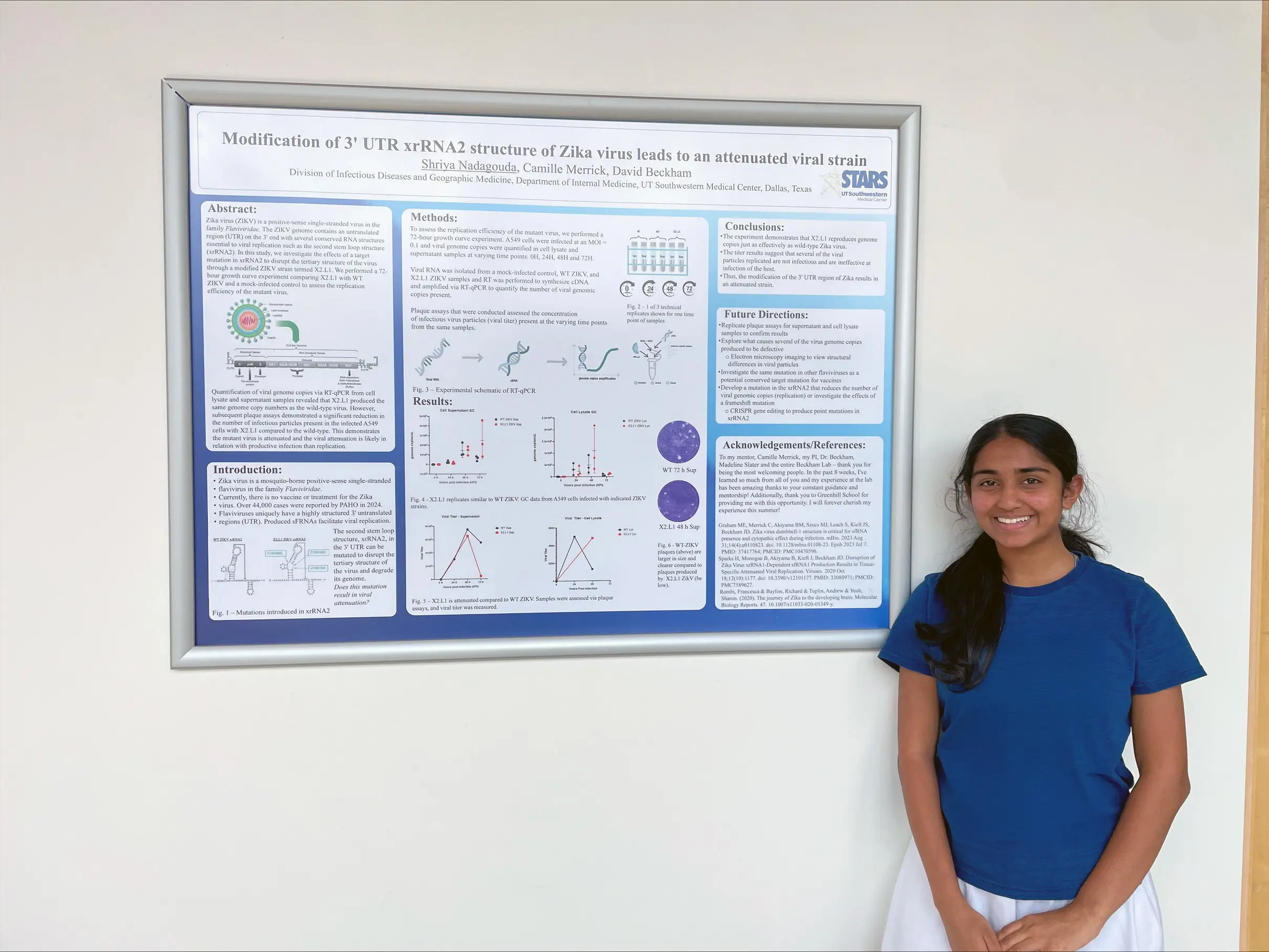

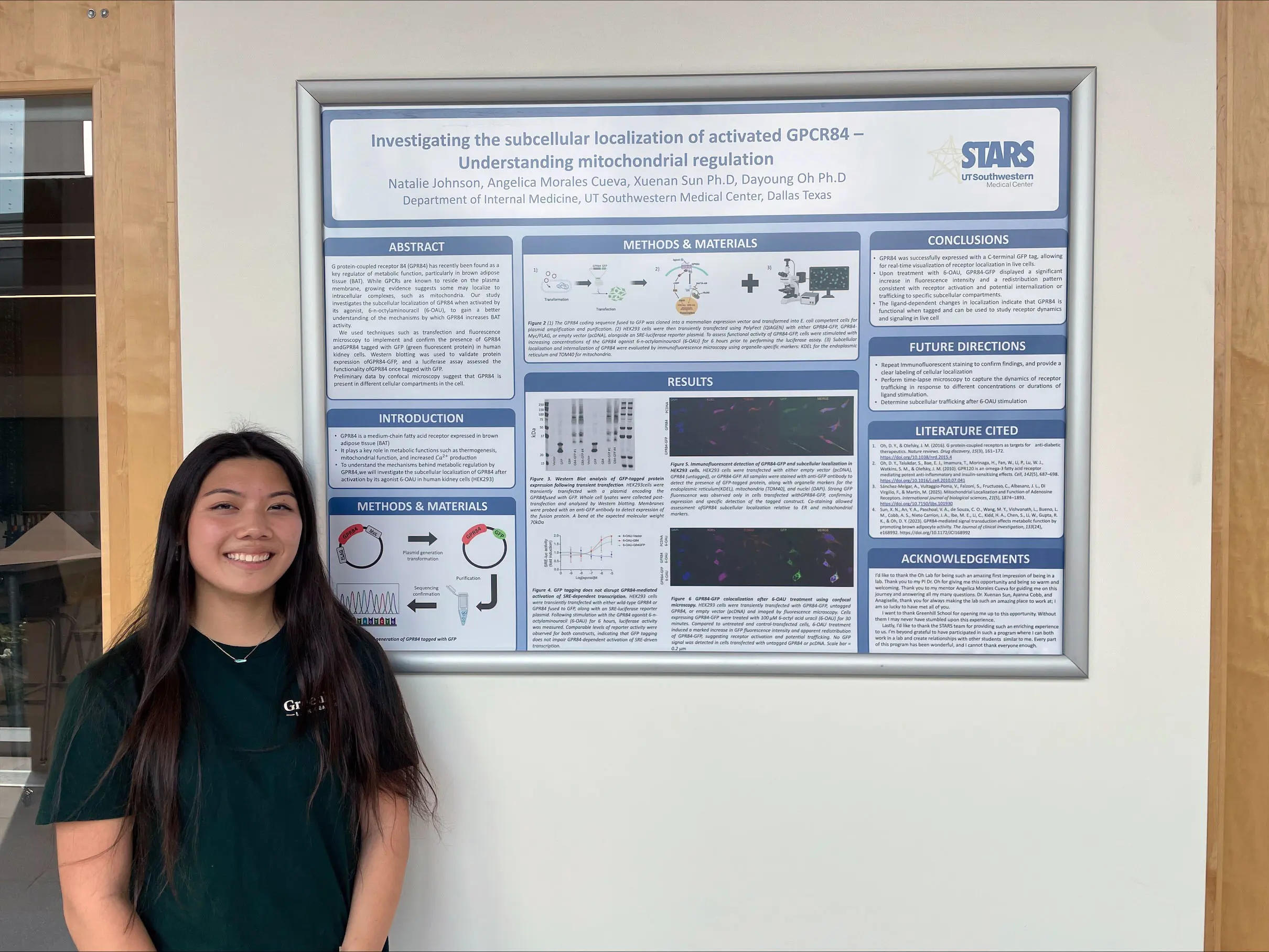

This past summer, seniors Natalie Johnson and Shriya Nadagouda spent full, paid workdays learning from their respective principal investigators and mentors.

“I think my PI did a really good job of preparing me to give my presentation,” Johnson said, using the shorthand term for principal investigators. “Every week, she would have me discuss what I’ve been doing for this project and what questions I may have.”

The STARS program is designed to give students without prior research experience or access to such opportunities a chance to work in a professional laboratory setting, according to Upper School science teacher Treavor Kendall.

“The great thing about this program is it will really give you a nice, legitimate, authentic introduction to that world,” Kendall said.

As the former Upper School Science Department chair, Kendall played a significant role in the STARS application process at Greenhill.

Selection for STARS is a multi-stage process.

First, students submit an application on the STARS website that incorporates written or video essays, teacher recommendations, personal statements and an experimental design. Then, the compiled list of applicants is sent back to Greenhill and reviewed by Upper School science teachers, who serve as the initial admissions committee.

The science teachers narrow applicants to five students who proceed to the interview stage with UTSW STARS faculty.

From there, the program generally accepts three students. This year, the third student had a conflict, leaving only two participants from Greenhill.

The application process is designed to give students room to explore their interests, according to Nadagouda, by pairing the students with a lab and PI consistent with their preferences.

“The ones that I ranked as my tops were neuroscience, molecular cellular biology and immunology, and I got paired with cellular biology,” said Johnson.

Kendall says the program is a big commitment for the selected students.

“I don't advise folks who are just sort of looking for something, not to be cynical, but something to put on your resume," Kendall said. “You really need to have interest in at least attempting to do research.”

Kendall says it’s difficult to thrive in the STARS experience without authenticity and self-drive.

“To be successful in the program, you got to be driving the thing,” Kendall said. “You're getting up at 7 a.m. in the summer. You're going to work. It is literally a job.”

Tracking

After being paired with cellular biology, Johnson tracked the cryptic movement of a cellular receptor known as GPCR84. While the receptor is typically found on the cell surface, Johnson’s lab investigated how activation triggers an unusual process in which GPCR84 migrates into the cell and the implications of that migration.

Johnson was placed in a lab that was a part of the Department of Internal Medicine in the Touchstone Diabetes Center. Johnson says she typically started her day at 9 a.m. and ended around 5 p.m.

The lab’s small, tight-knit team included a postdoctoral researcher, her mentor Angelica Morales Cueva, a doctoral student, a lab manager and recent high school graduates. The environment quickly fostered strong mentorship and bonding, according to Johnson.

Her research focused on G-protein coupled receptors or GPCRs, a type of protein involved in transmitting signals across the cell membrane. Johnson worked alongside her PI Dayoung Oh and mentor, studying how GPCR84 might affect metabolic regulation.

“My job was to figure out where, if anywhere, GPCR84 goes inside the cell after it’s activated by its agonists or ligands, keys that bind to the protein to trigger an action,” Johnson said.

She spent her summer using imaging techniques such as immunofluorescence staining and reading scientific literature to determine where the receptor traveled after activation, often finding herself stumped by inconclusive data and failed experiments.

“You may start out asking one question and barely scratch the surface for those eight weeks,” Kendall said. “Maybe you don’t even answer it but instead generate three more. That really is the nature of the work.”

Johnson says this reality quickly set in, but she came to embrace the trial-and-error process.

“[Oh] kind of pushed me a little bit, which was honestly really scary,” Johnson said. “At times, I definitely got a lot of things wrong, but I think it really helped me.”

The learning curve was steep, according to Johnson. With more exposure, she learned to solve problems and stay persistent.

“In terms of coming back from failed lab experiments, I was kind of wary at first because I’ve never been in a lab before,” Johnson said. “I was like ‘Oh my gosh! What is going on right now?’ but it’s pretty normal for experiments to fail.”

Johnson found it reassuring to discover where experiments had failed, and she says that Oh and Morales Cueva supported her throughout the process.

Zika Virus

Inspired by presentations given by STARS alumni, Nadagouda knew from her freshman year she wanted to apply to the program.

Nadagouda spent her time this summer studying Zika virus in the infectious disease lab with her PI David Beckham and mentor Camille Merrick.

“In my lab, we mutated the Puerto Rico Zika strain and the three prime UTRs, specifically the RNA structure xrRNA2,” Nadagouda said. “We made three-point mutations, and my project was focused on viral attenuation to see if that strain could become a possible vaccine candidate.”

Throughout her project, Nadagouda and the postdoctoral researchers in the lab met every week. She said Beckham specifically played a big role in keeping her on track.

“He asked me how my research was going, helped me prepare my poster and taught me a lot about the specificities of the virus,” Nadagouda said.

Nadagouda says she typically put in a six-hour workday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., during which she did experiments that took two to three hours each.

Nadagouda says these experiments altered her prior perception of being a researcher.

“A research environment is not like everyone does their own thing,” Nadagouda said. “While some people in my lab worked on the dengue virus or the Oropouche virus, we all came together and helped each other.”

Although newcomers start with less knowledge about research topics and procedures, they have access to a good support system, according to Nadagouda.

“You learn things through lots of years of doing it or just asking other people who have tried it,” Nadagouda said. “It’s a lot of guess and try.”

While gathering data for her final poster, Nadagouda says that she encountered problems with her RNA samples after cultivating and growing them for an extended period of time. However, she was able to turn this setback into a learning experience.

“I think overcoming [mistakes] is just realizing that everyone is going to make mistakes in the lab, and you have to think on the spot of how you’re going to fix it,” Nadagouda said.

Lessons Beyond Science

Though the STARS program is primarily focused on providing high school students with research experience in a professional setting, Upper School science teacher Barry Ide says that he has seen students, especially Nadagouda and Johnson, gain significant life skills.

“I can see their fluency and scientific literacy increase,” Ide said. “You know they’re more comfortable speaking. And I think that’s part of making presentations to their lab group, making presentations to other STARS students. All of that is effort and work, and it pays off.”

Although Johnson doesn’t intend to pursue lab research as a career, she says the experience taught her valuable lessons such as time management, communication and collaboration across various levels of knowledge.

“Sometimes when students go through the program, they’re like, ‘Yeah, this was really cool, and I’m glad I did it, and I don’t think I want to pursue this anymore,’ and that’s also growth,” Ide said.

Kendall says that regardless of the result, the process itself is a learning experience.

“What is the outcome and return? It is literally, not to be cliched, the journey,” Kendall said.